Finchbearer

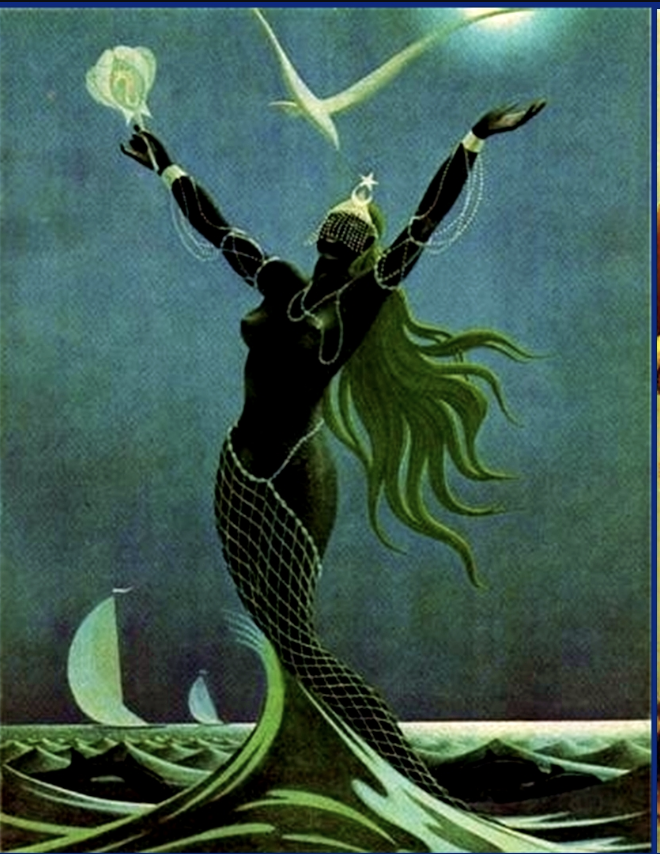

Istar

Istar

The witch is undoubtedly the magical woman, the liberated woman, and the persecuted woman, but she can also be everywoman.

Kristen J. Sollee, Witches, Sluts, Feminists: Conjuring the Sex Positive

What do we think of when we think of the witch? A woman burned at the stake? Religious fervour and fear of women? An old hag with a wart at the end of her crooked nose?

Think again. Witches are the everywoman. They have been fictionalised, sensationalised, and told and retold through storytelling for as long as stories have been told.

Here I present a compendium of witchy women. A sourcebook of complex and layered real and fictional women, who for the discerning fantasy writer may present a rich source of inspiration.

Some notes: this is a personal project for research purposes, however, I wish to share a shortened version of my findings, exclusively curated for Mythic Scribes.

The information sources are from my own existing knowledge and the internet. I’m not going to include citations. Conduct your own further research should you wish to. You may enter a discussion on this thread, but please be respectful.

Kristen J. Sollee, Witches, Sluts, Feminists: Conjuring the Sex Positive

What do we think of when we think of the witch? A woman burned at the stake? Religious fervour and fear of women? An old hag with a wart at the end of her crooked nose?

Think again. Witches are the everywoman. They have been fictionalised, sensationalised, and told and retold through storytelling for as long as stories have been told.

Here I present a compendium of witchy women. A sourcebook of complex and layered real and fictional women, who for the discerning fantasy writer may present a rich source of inspiration.

Some notes: this is a personal project for research purposes, however, I wish to share a shortened version of my findings, exclusively curated for Mythic Scribes.

The information sources are from my own existing knowledge and the internet. I’m not going to include citations. Conduct your own further research should you wish to. You may enter a discussion on this thread, but please be respectful.

Last edited:

Myth Weaver

Myth Weaver